We are book scroungers. Books of every age and provenance fill up bookshelves, trunks, and closets, and a few uncommon curiosities have made their ways into our ever-growing libraries over the course of the past three or four decades.

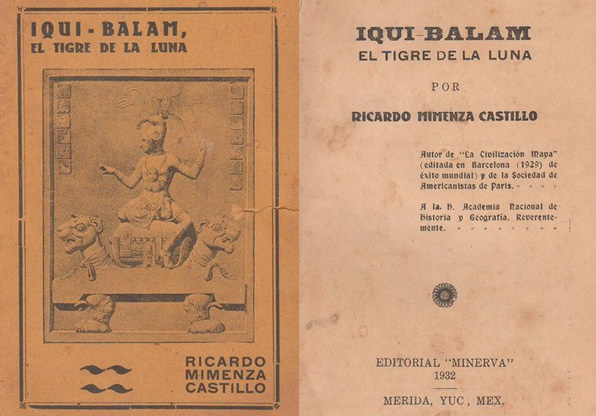

One of these is a small-format, ragged, and weathered booklet–almost more of a pamphlet–a mere 46 pages long, measuring 11.5 x 17 cm, and entitled Iqui-Balam, El Tigre de la Luna. The pages are darkened and stained by time and the elements and the front cover has come loose from the rusted staples still holding the rest of it together.

The booklet was written by Ricardo Mimenza Castillo, Yucatecan historian and poet, and published in 1932 by Editorial Minerva, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico. It appears to be a compilation of academic studies presented to the National Academy of History and Geography of Mexico as part of the requirements for the author’s acceptance into the academy. Also written by Mimenza Castillo is the Enciclopedia Grafica de La Civilizacion Maya (Lengua : Castellano).

The summary of Iqui-Balam reads (my translation): “About how Iqui-Balam or Ekbalam was one of the first settlers of ancient Yucatan according to the stories of Juan Gutiérrez Picón, colonial commissioner of Valladolid, and the Popul-Vuh.”

Below I have translated some excerpts from one of the chapters called, “Sources of our History,” detailing some of the most important academic sources of the day available for the study of the Maya.

The most ancient sources of the history of the Yucatan are the Mayan codices—the Troano, Cortesianus, Parisian, and Dresden codices [The Troano and Cortesianus, combined as the Tro-Cortesianus Codex, is now known as the Madrid codex]—the so-called Books of Chilam-Balam and Relaciones de Yucatán [Stories of Yucatan] made under the Royal Decree of 1557.

The codices were books written by the Maya on tree bark and in hieroglyphs containing their history and rites, their calendars and sacrificial rituals, etc., etc., interpreted by their Ah-kines or native priests. “Each sheet,” Brasseur affirms, “is illustrated on both sides with color images surrounded by or enmeshed with those black, so-called calculiform characters that the Maya in their tongue call ‘uooh,’ as opposed to ‘dzib,’ their word for images.”

Of these codices—many destroyed by the fanaticism of the missionaries—only the Troano and Cortesianus [ … ], the Dresden and the Parisian, remain …

The characters of said codices—despite intense study—are unintelligible even when attempting to read them with the Mayan alphabet of Landa …

Such is not the case with the Books of Chilam-Balam, which have provided valuable and special aid to Americanists in pre-Columbian matters; the books, written in the Mayan language but with Spanish characters, summarize events before the Conquest. […] The books were composed between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, and Dr. Gordon of the University of Pennsylvania has made paleographic reproductions of some of them.

The Popol-Vuh or Sacred Book of the Quiché Peoples also sheds not insignificant light on the protohistory of the Mayas and their nebulous origins. In 1923, under the aegis of the unforgettable Felipe Carrillo Puerto, we put out an edition of this book in the Yucatan.

On the back cover of the booklet is a florid inscription, part of an old advertisement. It reads (my translation), “In the train, on the boat, on the beach, in the country, always carry a book.” It is the advertisement of La Literaria bookstore situated on Calle 50, Parque Hidalgo, Apt. 203 (surely this was an address in Merida, where the booklet was published).

As a supreme bonus, from between the fragile and yellowed pages appeared a ten-centavo punched transport ticket, undated, printed with the name of I.N.B.A. (Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes–the Institute of Fine Arts) and the Conservatorio Nacional de Música (National Conservatory of Music). The ticket states that it was “good for one fare” but does not indicate what kind of transport.