How a mining company expedition in the early 1820s spawned and fueled Mexico’s passion for the sport of football soccer.

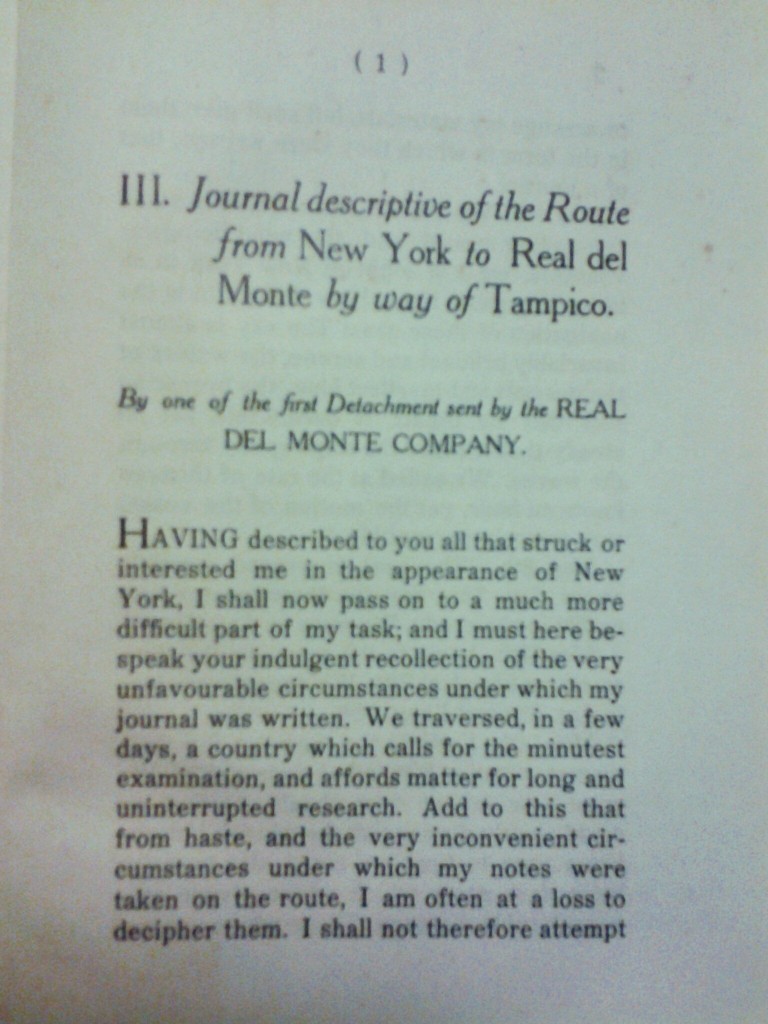

A synopsis and excerpts from III. Journal descriptive of the Route from New York to Real del Monte by way of Tampico by one of the first detachment sent by the Real del Monte Mining Company, July 16, 1824.

This is another book in our eclectic library, an astonishing account of an expedition into old Mexico that gives us glimpses of the country as it grew toward being a modern nation.

FYI

Real del Monte, also known as Mineral del Monte, is a mining town in the Mexican state of Hidalgo, about 120 kilometers from Mexico City. From the mines of the region (the mining district of Pachuca), gold and silver have been extracted since the time of the Spanish conquest.

Mineral del Monte was named a Pueblo Mágico de México by the Mexican government in 2004 because of it’s historical importance, colonial architecture, and rich culture and traditions.

“Cornish Mining in Mexico,” on the Cornish Mining World Heritage website at http://www.cornish-mining.org.uk/delving-deeper/cornish-mining-mexico, tells us that the Real del Monte mines were purchased by Real del Monte Mining Company after Mexico’s War of Independence. An important Cornish community resulted from the migration of Cornish miners into Real del Monte and the entire Pachuca mining region of which Real del Monte is part. The miners brought with them and continued to practice many of the favorite aspects of their homeland culture, including sports and food preparation, and these today are part of Real del Monte’s and Mexico’s rich heritage.

These Cornish miners, who formed Mexico’s first football soccer club in 1901, spawned and fueled the passion and enthusiasm that Mexico now holds for the sport of soccer.

A synopsis of the travel report written in 1824

This short journal appears to be a report to the mining company about the detachment’s arduous journey from the gulf coast into the Mexican interior and highlands in 1824 and its observations about the mining district once the detachment arrived at their destination of Real del Monte.

It starts off with the boarding of the mining company detachment in New York onto small, fast, unnamed sailing vessel on May 4. The writer, also unnamed, describes making a good thirteen knots an hour out of New York under stable conditions. Journal entries for the first several days are few and short, dealing mainly with the increase in temperature as the boat approached the tropics.

On May 16, having just passed Cuba and moved into the tropics, our author writes of a tremendous phosphorescence: “Our swift vessel dashed up thousands of sparkling drops and left behind a long track of light. Further on, the tops of the distant waves might be discerned fringed with light, or billows breaking against each other threw up a cloud of brilliant spray against the darkness.”

Arriving finally at the bar of Tampico, the author, while awaiting a pilot boat to bring the ship into the mouth of the Rio Panuco, seems as unimpressed by the construction of the fort guarding the entrance to the bar as he is by the appearance of the natives. He describes the fort as “Four old trunks of trees [ … ] stuck in the earth so as to support a rude sort of lattice-work, or hurdle, upon which a nearly naked soldier mounts guard.” Some of his depictions of the natives’ appearance and their dress or lack thereof are so pejorative that I wouldn’t dare to repeat them here.

The detachment and baggage were transferred into canoes and poled upriver toward Pueblo Viejo de Tampico. The author’s words sketch for us the journey inland, the novelty of the new land shining through as he describes the tangled mangroves and the richness of the wildlife. He marvels at the pendulous nests of the yellow-winged Mexican cacique: “They are in the form of a long purse, at the bottom of which are deposited the eggs; a hole near the top serves as a door, but it is placed on the side in order that the rain may not penetrate through it.” We see a lot of those same nests around Zihuatanejo, hanging precariously from branches over both back roads and highways.

The detachment’s arrival in Pueblo Viejo de Tampico was met with great suspicion on the part of the local commandant, who questioned the party thoroughly. He had heard a rumor that the ship from which they had debarked might have been carrying Spaniards with subversive intentions.

While awaiting authorization to move on, our author explored Pueblo Viejo. “I seemed to be wandering in a botanic garden richer than any I had ever beheld, and every plant, every blade of grass, reminded me that I was indeed in a New World.” In his walks, he was regaled by the calls of parrots, surprised at their tameness, and was set upon somewhat viciously by swarms of flying insects and red ants.

On May 27, the contingent finally began its trek inland with a caravan of over forty mules. Divided into two segments–one of fast-moving horsemen who went on ahead and the other, including our man, of baggage tenders on the slower-moving mules–they passed the city of Tampico and carried on through the lush and verdant countryside. They stopped on the first night to dine and overnight at Los Ranchos de las Tortugas, where our author describes a night filled with fireflies of a kind quite different from any he’d seen in Italy: “[T]hey are not properly flies [ … ] and their light is not situated in the abdomen but on the sides of the thorax. This light, also, instead of being pale and yellowish, is blue and very brilliant.”

Thereafter come days of trudging through persistent and increasingly heavy rain. Every night, the caravan stopped at ranchos along the way where they were made welcome and given shelter, this at times being only a place to hang their hammocks under the roofs of livestock sheds.

The author’s account of the trek of May 28 details a change in vegetation, the appearance of different types of palms, and the screech of what can only have been cicadas, “a most abominable sort of cricket [that] never ceased for one instant to persecute our ears.” That night, the contingent stayed at Rancho de Bicin.

Our man’s description of the night of May 29 spent at Rancho de Buena Vista amongst swarms of ticks, which he calls “garrampatos,” (they are really garrapatas) is truly terrifying. “Not the army of Xerxes, not that of the Myrmidons, equalled in numbers the swarm of garrampatos which poured down upon us. I passed the night without closing my eyes …”

On May 30, the mule train arrived at–and had to cross,with mules and baggage–the raging torrent of Chicayan, a feat of endurance that took them almost the full day to accomplish. They bedded down that evening at Rancho Los Alacranes, only an hour beyond the torrent. Near the ranch house was “an enormous mound of earth of a semicircular form, so regular that it is evidently a work of art,” that could only have been a remnant of an ancient indigenous settlement. Our author doesn’t elaborate or speculate much on this finding.

On that eve of May 31, our author tells us that “our muleteers began a serenade; it consisted of extempore compliments to us, sung after the Spanish fashion, and accompanied on an old guitar which they found in some corner of the house.”

That, to me, sounds just the way things still are here in Mexico today–a spontaneous outpouring of experiences and emotions punctuated by the chords of an old guitar.

In the next post, I’ll carry on with a the second half of this fascinating account of a journey from the gulf of Mexico into the central highlands of the country, covering May 31 to June 13, 1824.

Route taken by the Real del Monte Mining Co. detachment in 1824.